Malaria is on the ropes in Bangladesh. But the parasite is punching back

By Ari Daniel

Bulbul Aktar, a s, or community health worker, with the malaria elimination program in Bangladesh, goes door to door to treat malaria patients. "This is my job, my duty," says Aktar. "Every single home, I have to know about them and visit them." Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRBulbul Aktar, a s, or community health worker, with the malaria elimination program in Bangladesh, goes door to door to treat malaria patients. "This is my job, my duty," says Aktar. "Every single home, I have to know about them and visit them."

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRThe soft footfalls of thousands of moccasins along unpaved rural roads across Bangladesh could be considered the soundtrack to this country's astonishing success in its battle against malaria.

On one Friday morning in December, a pair of those moccasins belongs to 42-year-old Bulbul Aktar. Here in Chakaria, in the southeast of the country, she's visiting every home in this small community by foot. It's a crucial task given the historic difficulty of gaining ground in the fight against malaria — a fight that could soon be flaring up once more.

Wrapped in a crimson shawl, Aktar approaches one of the households and shouts the standard greeting: "As-salamu alaykum!"

Asha Gudin lives here with his family. A month earlier, after working a construction job a few miles away along the border with Myanmar, Gudin spiked a fever and felt awful.

Bulbul Aktar is one of thousands of community health workers in Bangladesh — all of them women — who to go door to door to diagnose and treat people for malaria. Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRBulbul Aktar is one of thousands of community health workers in Bangladesh — all of them women — who to go door to door to diagnose and treat people for malaria.

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRSo he sought out Aktar. She's what's called a — a community health worker. Bangladesh employs thousands of these workers, all of them women, to go door to door to treat people for malaria, a disease transmitted by mosquitoes.

"This is my job, my duty," says Aktar. "Every single home, I have to know about them and visit them."

When Aktar tested Gudin for malaria, he was positive. So she gave him a drug called artemisinin.

"That night, I called him," she says, to see "how he's feeling and [if] he took his drug properly or not. After that, I called him every day at 10."

Over the three-day regimen, Gudin made a full recovery.

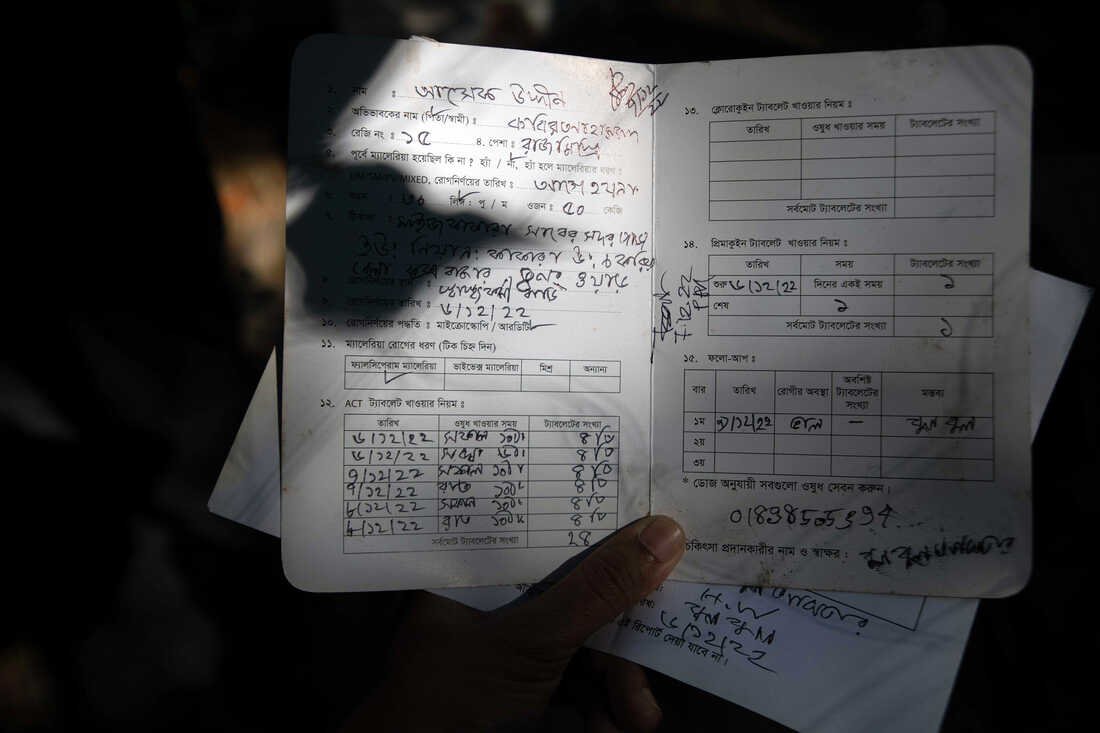

Asha Gudin, a malaria patient in Bangladesh, made a full recovery in three days, thanks to a quick diagnosis from a local health worker and an effective drug called artemisinin. Here, Gudin displays his treatment card. Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRAsha Gudin, a malaria patient in Bangladesh, made a full recovery in three days, thanks to a quick diagnosis from a local health worker and an effective drug called artemisinin. Here, Gudin displays his treatment card.

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR"It's really pretty remarkable," says , a microbiologist at the University of Notre Dame who studies the malarial parasite. "I mean, [the shasthya kormi] find the malaria. That's what it comes down to. And then they treat it, one person at a time, one family at a time. And then if it comes back, they come back. They're the foot soldiers of this fight."

Gudin isn't alone in his healing. Health workers say artemisinin almost never fails. "This drug is a marvelous drug. It's a perfect drug," says who's devoted his life to treating patients with malaria in Bangladesh. (There is a malaria vaccine that's been deployed in parts of Africa, but Haldar says it won't yield rapid elimination.)

Dr. Ching Swe Phru helps disperse bed nets treated with insecticide. Phru is grateful for the strides made against malaria but adds, "I'm afraid that malaria has a certain history of coming back." Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRDr. Ching Swe Phru helps disperse bed nets treated with insecticide. Phru is grateful for the strides made against malaria but adds, "I'm afraid that malaria has a certain history of coming back."

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR"You have to be alert," says Dr. Phru. "You have to be afraid of it. The parasites always have an inborn tendency to fight off the killing drug."

It wouldn't be the first time.

"I'm afraid that malaria has a certain history of coming back," says Phru.

Malaria is ancient but has an expanding footprint

The malarial parasite has plagued humanity for thousands of years. That history is written into our blood, which has evolved strategies to defend itself — think sickle cell disease and other kinds of anemia, which themselves can cause illness but also convey protection from malaria. "Our blood has been profoundly shaped by malaria infection," says Haldar.

Despite centuries of battling the disease, people continue to get sick from malaria, with more than 600,000 deaths every year, mostly in Africa. And its footprint is as our climate changes, allowing the mosquitoes that transmit the disease to thrive in previously inhospitable regions, such as the higher altitudes of Ethiopia, Colombia and parts of Asia.

Bed nets treated with insecticide to ward off mosquitoes are distributed in Chakaria, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRBed nets treated with insecticide to ward off mosquitoes are distributed in Chakaria, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR"High fevers, chills and severe headaches, vomiting and nausea," he says. "The nausea was the worst. I couldn't study. My partner would recite me all the studies, and I would listen to him. And then I went for the exam with 101 or so Fahrenheit of fever. So I had to face it."

Phru was treated with a couple of drugs, including one called chloroquine. "It's a very nauseating drug and a terrible drug," says Phru. Despite the rough side effects, he was cured.

For decades, chloroquine was one of the most valuable malarial treatments worldwide. But then, gradually, the parasite stopped responding. It had developed resistance to chloroquine.

That resistance originated in southeast Asia and spread through Bangladesh to Africa until it was pervasive.

"We consider our region an important route for transmitting drug resistance," says , a parasitologist from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (known as icddr,b).

The resulting fatalities , hitting sub-Saharan Africa especially hard in the 1980s. "If you don't treat people quickly," says Alam, "they may die."

That's when doctors turned to artemisinin, a compound purified from the sweet wormwood plant in the 1970s. It had taken decades to puzzle out how to make it, deliver it effectively and produce it affordably. Once the drug became available, health workers in Bangladesh were so hopeful they created a whole infrastructure around it to support the thousands of community health workers.

Community health worker Bulbul Aktar handwrites her notes to keep track of the spread of malaria. Fatima Tuj Johora for NPR hide caption

toggle caption Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRCommunity health worker Bulbul Aktar handwrites her notes to keep track of the spread of malaria.

Fatima Tuj Johora for NPRThe current set of samples may not tell the whole story, however. Not everyone with malaria ends up at the clinic, so it's possible there are resistant parasites circulating unnoticed in the population.

To that end, Haldar is considering enlisting the shasthya kormi health workers to collect more samples from people within the community to expand the hunt for resistant malaria. That will help her and her team get a better lock on how prevalent the disease is, identify the mutations that may be causing the resistance and then look for different drugs the parasite hasn't yet outsmarted.

Haldar is playing the long game against those parasites, one that won't be won easily. "They're complex," she says, "and they deserve your respect."