The microbiologist studying the giant floating petri dish in space

By Aaron Scott|Rachel Carlson|Rebecca Ramirez

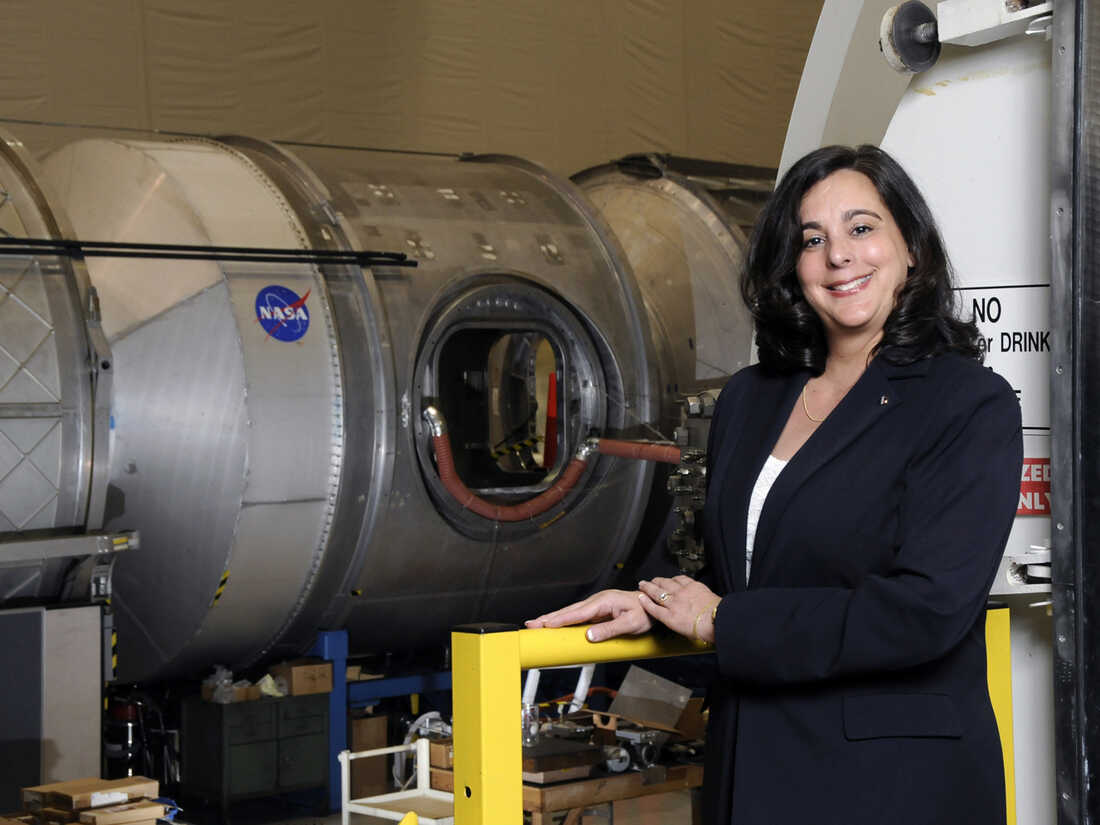

Microbiologist Monsi Roman stands next to an ISS Life Support test module at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. /Monsi Roman hide caption

toggle caption /Monsi RomanMicrobiologist Monsi Roman stands next to an ISS Life Support test module at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center.

/Monsi Romanjoined NASA in 1989 to help design the International Space Station. Just a few years removed from earning her masters degree in microbial ecology, she was tapped to become the chief microbiologist for life support systems on the space station. The team's first task was building air and water recycling systems for a crew that planned to stay up to six months in space.

Roman says they were taken aback.

"For the first time, we were going to be recycling the water for the crew to drink. And when I mean recycling, we were going to be using the urine," Roman says. "You know, that is pretty nasty."

A microbial detective game

Beyond figuring out what kinds of microbes would grow in tanks full of urine, condensed sweat and shower water, Roman and her team had to address another microbial threat: biofilms. Around the time they were conducting tests for the ISS, rumors were circulating that biofilms, or communities of microbes growing on surfaces, had started eating away at the Russian Space Station.

Engineers on the team said the solution was straightforward: Make the space station sterile.